articol preluat de pe www.pt-magazine.com

Aging Tobaccos

What types of tobaccos most improve, what methods work best, and what really happens when you age your tobaccos

by Tad Gage

Buying pipe tobacco with the specific intent to set aside a certain number of tins to be consumed at a future date is a relatively new phenomenon. Even purchasing old, unopened tins of tobacco with the idea not only of smoking a blend no longer created, but experiencing the changes that have occurred to it, is fairly recent.

It might have started with Robert Rex of the venerated Druquer & Sons Tobacco Shop in Berkeley, Calif. In the late 1970s, Rex was setting aside new tins of tobacco, letting them age five years, and then selling them as five-year matured blends (at a premium price), recalled tobacco blender Greg Pease, who worked in the shop.

However and whenever the practice of aging tobacco actually began, many tobaccophiles have discovered the benefits of setting aside newly purchased pipe tobacco for several years. Additionally, the fact that numerous old tins of unopened tobacco have survived for several decades has enabled pipe smokers to sample the effect that extreme aging has on tobacco.

I consider this article the third in a series begun in 1999, when Pipes and tobaccos Editor Chuck Stanion authored two excellent articles: the first detailing the extensive chemical and biological changes that occur when processing tobacco leaf and readying it for blending, and the second on the whys and wherefores of building a stockpile of tobaccos for the purpose of aging.

I highly recommend that you track down these two articles to get additional detail. The article on tobacco processing was in the Winter 1999 issue, which is unfortunately sold out. The cellaring article in the Spring 1999 issue is still available. I’ll summarize a few salient points from these articles so you don’t have to go digging for them right this minute.

After an appropriate aging period of eight years between Stanion’s articles and this one, we’re as ready as we’ll ever be to delve into the final aspect of the evolutionary tobacco aging process—what happens to pipe tobacco blends in the months and years after they’re blended, and bagged or tinned. The experiment with how tobaccos age, and Joe Harb’s and my sampling of these blends, provides the perfect setup. I might add that this aging experiment, which showed amazing foresight on the part of Pipes and tobaccos magazine, has changed the way I’ll age my pipe tobaccos. I outline this at the end of my article. You can teach an old dog new tricks if that old dog is willing to learn.

This article doesn’t examine the effects of aging on cased (flavored) aromatic tobacco or black Cavendish tobaccos. If you have high-quality base tobaccos, such as Danish Virginia-based blends, they may undergo changes similar to unflavored Virginias. But it’s difficult to judge the effect of flavorings on the aging process, so I won’t go there. If you like particular aromatic blends, you should be able to store them successfully. I’ve noted that changes have occurred to old flavored blends such as Erinmore and Three Nuns, but it’s the base tobaccos that change, not the flavorings themselves.

The initial stages of processing tobaccos and preparing them for final use involve extensive chemical changes brought about by various combinations of heat, pressure, microbial action and environmental factors. In simple terms, the goal is to cure the tobacco to remove undesirable, bad-tasting compounds such as ammonia, convert bland starches into tasty sugars, and allow the leaf to mellow and ripen in flavor. I recommend the Winter 1999 Pipes and tobaccos article for a detailed explanation of this process.

Even after growers and processors are finished with the leaf, blenders may take the tobacco through additional steps before ever presenting their products to the public: aging, roasting, toasting, stoving, heating, pressing, slicing, dicing, spinning, rolling, twisting and even flavoring. Some of these processes, like pressing cured leaf into cakes under pressure, create dramatic changes. Other processes, as with Perique tobacco, which involve squishing the tobacco under incredible pressure, forcing out moisture and oils, then allowing it to be absorbed again and again, lead to a new and transformed product. And then there’s simply allowing tobaccos in bulk to rest for months or years in a warehouse before being turned into pipe tobacco blends, a process that fosters subtle but important changes.

However, once the tobacco is turned into a final blend (whether cut into ribbons and mixed, or sliced and left as a whole flake, or something in between), ready for sale, it takes an evolutionary right turn. It continues to mature and develop, albeit far more slowly than in the initial stages of processing. The new element in this branch of the evolutionary tree is that individual tobaccos have been brought together, much like a pair of individuals who marry. They continue to grow as individuals, yet they also grow and mature together. Each tobacco used in a blend may have begun life as an individual entity, but once blended into a final product, it becomes a team player.

“Aging pipe tobacco blends represents the final stage in a fascinating organic process that started the moment a leaf was harvested,” says Pease, who has earned acclaim for his GL Pease pipe tobacco blends and also his erudite discussions on tobaccos. “There are scientific explanations for what happens once a blend is created and starts to age, but in many ways it’s as much magic and mystery as it is science, because each blend ages in its own unique way.” He notes that there are so many variables involved that it would require extensive scientific research to explain. Personally, I like “magic.”

It’s entirely likely that even various vintages of the same blend will age differently, based on differences between the tobacco crops used from year to year. Although blenders strive for consistency from batch to batch and year to year, the base tobaccos used may vary in quality or character. Other variables also impact how quickly and well pipe tobacco ages, and I cover these later in the article. Pease notes that a basic rule of organic chemistry applies to the aging of pipe tobacco blends—each time a new variable is introduced, a chain reaction will take off in a different direction.

“If you were to age three tobacco components separately for several years, then combine them, you would have a very different tasting outcome than if you were to combine these components in the beginning and age them together for the same number of years under the same conditions,” he explains. “Organic reactions are continuous and build on each other. Based on a wide number of variables, these chain reactions can take an almost infinite variety of paths. Any time a new variable is introduced, whether it’s storage conditions, or the conditions under which the tobacco was first blended, or the specific leaf used, the potential exists for an entirely different direction that the organic reaction can take.”

None of the tobacco enthusiasts I’ve discussed this subject with are aware of any thorough scientific studies on the exact changes that can and do occur in pipe tobacco blends. That’s not likely to happen, either, since you’d need extensive numbers of controlled samples and about 10 years to complete the test. And it would probably be tough to find a research grant, anyway. “Informed conjecture” is the operative phrase when dealing with what happens as pipe tobacco ages.

The Winter 1999 Pipes and tobaccos article contains an excellent scientific explanation of what happens to tobacco as it ages: “‘Tobacco leaves have little hairlike structures on them, and these hairs produce certain gums containing terpenes—a class of chemical compound responsible for aroma, similar to beta carotene, pine pitch and menthol,’ explained Dr. David Danehower of the University of North Carolina. ‘These terpenes contain compounds called duvatrienediols, which contribute to the characteristic flavor and aroma of tobacco.’ The way duvatriendediols contribute is by breaking down as they age.”

There’s further discussion in the article of how various elements in pipe tobacco evolve, break down and combine, including the Maillard reaction. I could easily quote the entire article to give you more science, but let’s accept the premise that interesting and complex chemical and biological changes take place as tobacco ages, and that there is a scientific explanation for all of it. My focus is what you should expect as your tobacco ages, and what you can do to control or predict what’s going to happen.

My personal cellar contains tobaccos ranging from new purchases to tins that are at least 40 years old. I was turned onto the delights of aged tobaccos by the late pipe and tobacco dealer Barry Levin. His access to old tins owned by pipe collectors and stores gave him an unusual opportunity to purchase and sample long-aged pipe tobaccos. I worked with Levin to formulate some of his blends, especially Latakia blends, since he smoked and liked only Virginia tobaccos. Levin worked with McClelland Tobacco Company to turn his Personal Reserve Series into reality, and his excitement over the impact of aging was felt there as well.

“I was turned onto the idea of the effect of aging tobaccos in the tin by Barry, who used to send me old tins and tell me to check out what had happened to the tobacco over the years,” says Mike McNiel of McClelland Tobacco Company. “He was so excited about this, and when I tried these blends, it was an eye-opener. They had developed, matured, changed.”

McNiel, who intimately knows the business of buying and creating tobacco from the ground up (literally), was already familiar with the impact that curing, processing and aging has on tobaccos before they’re tinned or otherwise packaged. He noted the concept of further aging tobaccos in the tin added a new dimension to the company’s approach to producing pipe tobacco blends.

“Very few, if any, [pipe tobacco] manufacturers or blenders throughout history have been concerned with what happened to their tobaccos after tinning,” McNiel explains. “The product was created to be consumed and enjoyed immediately.”

And the best blends were, I’m sure, simply fabulous right out of the tin. Over the years, I’ve talked with enough “old pros” who were able to purchase and smoke classic blends like Balkan Sobranie 759, Baby’s Bottom, John Cotton’s Smyrna, Scottish-made Three Nuns, old Capstan, Lane’s Crown Achievement from the 1960s and many more when they were still being manufactured.

It takes a considerable amount of money and space for a manufacturer to hold tinned tobaccos for future sale. Most can’t or won’t make that investment. McClelland, never shy about raising the bar, has made that commitment.

The Magic of Three

McClelland is one of the few manufacturers to date-stamp its tobacco tins, giving us the opportunity to know exactly when a blend was tinned. “We [Mike and Mary McNiel, owners of McClelland] have for many years let our tinned blends age for at least a year, and two years if we had enough supply,” says Mike. “We’ve been convinced of the positive effect of aging blended tobaccos. I wish we were able to age our bulk tobaccos in the same way, but we need to move it to shops.” I have some ideas for successfully aging bulk tobaccos, which I’ll share later.

McNiel notes that McClelland has been building inventory of its tinned blends and is now in the fortunate position to wait three years after tinning before releasing blends for sale. “Previously we haven’t had the inventory to hold blends back for more than two years,” he says. “Now we do, and I believe three years is a magic number for maturing tobacco in the tin.”

McNiel and I discussed the outcome of the experiment involving his blends, which underscored his belief that significant changes occur to many blends between the second and third year of cellaring. “I’m excited because this is something that has never been done before,” says McNiel. “I know of no manufacturer who has set aside tinned tobaccos for three years before selling them.”

If you take nothing else away from this article, it should be that if you buy tobaccos you like, with the intent to let them age, three years is a magic number. Good tobaccos should evolve (positively) with age, depending on how they’re stored. At worst, they won’t change significantly or deteriorate in flavor within three years. It appears that three years is long enough for any tobacco blend that is going to evolve to do so, although certain blends will evolve for decades. Yet three years isn’t so long that any blend will begin to decline in flavor or quality.

Tobacco can continue to change for at least 20 years, but as time passes, the changes become more subtle. Certain tobaccos may decline in flavor after 10 years. We’ll address that later. But consider that three years will be an optimum time for any fine blend you purchase to undergo any notable aging it is likely to undergo.

Greg Pease notes the positive difference that a minimum aging of three years can produce. He frankly admits that his own blend, Kensington, was not one of his personal favorites. His refined palate told him that this blend was missing something. However, after opening a three-year-old tin of Kensington (a mixture of Virginia, Oriental and Latakia tobaccos), he found the change he hoped for. “In the bowl, this stuff is remarkable. The time has transformed it into a truly wonderful, ripe, complex blend.

“The aroma … beneath the smoky campfire notes of the Latakia, provides delicate tones of lavender and basil, pronounced fruity aromas of apricot jam and fresh, ripe plums, and woody mid-tones that remind me just a bit of some exotic hardwoods like Padouk. I could spend hours just sniffing this stuff. I nearly did.” After three years, this was a much different blend that it was when it went into the tin.

Scientifically, Pease notes the Maillard reaction explained in the 1999 Pipes and tobaccos article: an interaction of aldehydes and amino acids to produce pyrazine, which is present in appealing aromas like roasting nuts and popping corn. Of course, there are many other odors that occur as a result of aging. Pease’s assessment of the positive changes his own blend underwent underscore how a few years of aging can affect pipe tobacco.

The Best Tobaccos and Blends for Aging

The best way to explain the effect of aging on various tobaccos is to describe a personal experience—one that’s similar to Pease’s in that the blend I discuss is also a mixture of Oriental, Virginia and Latakia tobaccos.

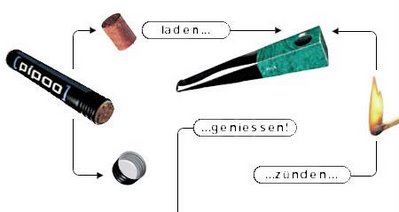

As I’ve developed this article, I’ve been smoking some Rattray’s 3 Noggins “Full” (a blend with more Latakia than plain 3 Noggins) that is at least 20 years old. It was given to me by my friend David Sahagian, who in true pipe-lover style gets more pleasure from giving a tin of rare and expensive tobacco to a friend than selling it. Like Pease’s tin of Kensington, the lid on the sealed tin of 3 Noggins was puffed out rather than flat or even slightly concave, as it was when the can was originally sold. Even a novice can easily see that something biological and/or chemical has taken place.

The ancient Rattray’s blend I’m smoking has, I’m sure, a very different character than when it was first sold. The Syrian Latakia has remained firm in flavor, but it has softened a bit. The Oriental tobaccos have developed a touch of sweetness and complexity. The Virginia tobaccos have matured, sweetened and shared their flavors with the Latakia and Oriental leaf. It is outstanding—different than the original creation, which I’m sure was delicious. I’m guessing the evolved tobacco is better than it was when tinned.

Although the tin was vacuum sealed to some degree, it had puffed up a bit, indicating there is, or had been, enough oxygen inside the tin to allow the activity of yeast, enzymes or bacteria. The living organisms inside had air, allowing them to consume residual amounts of cellulose (starch) in the tobacco and convert it to sugar, releasing carbon dioxide in the process and increasing the pressure inside the tin. That’s the most likely explanation for why certain tins of tobacco puff out over time.

Using the old Rattray’s tobacco as a springboard for further discussion, let’s review how aging tends to affect the major categories of tobacco used in pipe tobacco blends. The Spring 1999 issue of Pipes and tobaccos thoroughly discusses how dramatically the basic types of pipe tobacco leaf age, so I’ll make this a very brief summary.

P&T